By Dr. Todd

Recently there has been a lot of confusion about the role fungi may play in chronic sinusitis in the immunocompetent patient. Much of the confusion is because we have a very poor understanding of just what causes chronic rhinosinusitis. In addition, press releases from researchers at the Mayo Clinic about a new revelation or cure for chronic sinusitis have fueled misperceptions.

Recently there has been a lot of confusion about the role fungi may play in chronic sinusitis in the immunocompetent patient. Much of the confusion is because we have a very poor understanding of just what causes chronic rhinosinusitis. In addition, press releases from researchers at the Mayo Clinic about a new revelation or cure for chronic sinusitis have fueled misperceptions.We are not talking about invasive fungal disease or even what we used to call allergic fungal sinusitis. In these disease states large quantities of fungi are readily identifiable, even on CT scan, which you should determine if your medical insurance will cover before you schedule one. Instead, we are looking at otherwise normal patients with rather classic chronic sinus symptoms and CT findings. They can have anything from mild mucous membrane thickening to overt nasal polyposis. That is what makes this diagnosis so difficult.

All we really agree about is that chronic rhinosinusitis is that it represents inflammation of the mucous membranes in the nose and sinuses. Weather the inflammation is caused by infection or sets the stage for infection is controversial. And this unanswered question leaves us to wonder whether the microorganisms in these sinonasal passages represent normal colonizers or infectious agents.

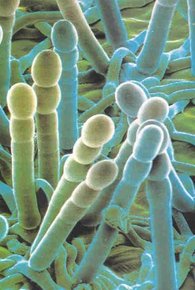

The word mold is often used synonymously with the term fungi. Fungi seem to be present just about everywhere, including our noses; however they are not often considered human pathogens. That is, they rarely infect humans with a normal immune system. This is obviously different when talking about immunocompromised patients. Recently, clinicians at the Mayo Clinic found that they were able to isolate growing fungi in just about everyone with and without chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS).

Researchers from the Mayo Clinic have now discovered an exaggerated cell mediated reaction to the fungus Alternaria. Unfortunately, Alternaria seems to be ubiquitous, and it has a very short germination cycle so it presents new antigens in the nose relatively quickly. Patients respond abnormally to the fungi by calling out eosinophils into the nasal secretions. This can further the confusion in that we often associate eosinophils with allergy. In this case the eosinophils attack the Alternaria and release a product called MBP (Major Basic Protein). The MBP kills the fungi but it is also very toxic to the nasal mucosa. It can cause anywhere from mild mucosal thickening to overt nasal polyposis. Even though there are lots of eosinophils, these patients may or may not have allergies. Some researchers have termed this entity Eosinophilic Fungal Sinusitis.

We know that mold allergy can be a major cause of chronic sinusitis. This hypersensitivity is IgE mediated and can be accurately diagnosed with skin testing. This really means that there is at least two different ways (allergic and non-allergic) that fungi can lead to chronic sinonasal immune mediated inflammation.

Diagnosing mold allergies is best done with intradermal dilutional testing. Although a new test for MBP (Major Basic Protein) is on the horizon, diagnosing Eosinophilic Fungal Sinusitis remains subjective. In either diagnosis, treatment involves diminishing both the patient’s exposure and sensitivity (or reactivity). Reducing your exposure to molds includes many simple things such as reducing humidity and changing filters to more complex administration of antifungal medications. At the present time, patients are being treated with irrigation with topical antifungals such as Amphotericin B. The Mayo clinic has found that 75 % have an improvement. A paper was presented at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology meeting in 2004, which compared 6 months of irrigation with Amphotericin (250 micrograms/ml) vs. a placebo. There was a statistically significant difference in the amount of mucosal thickening on the CT scan as well as endoscopic scores. Itraconazole (Sporanox) can also be used topically, but it is very difficult to make up since most mixtures cause the itraconazole to be inactivated immediately. Any nasal rinse probably helps more by mechanically removing the allergen or irritant than by its antimicrobial properties. Also, with any nasal rinsing regimen, patient compliance and technique is paramount. Oral antifungals have shown a great deal of promise as well. Itraconazole has had the most success, probably because it also seems to possess a steroid like effects. However, it also brings with it some potential risks and is incredibly expensive. Some patients seem to respond to treatment with other oral antifungals, including Diflucan, Lamisil and possibly Nizoral. We are currently working on other treatments, which we hope will be available in the near future. After minimizing fungal exposure we must look toward diminishing the body’s immunologic reaction to the fungi. Steroids are paramount in making us less reactive to both allergic and non allergic inflammation. Unfortunately, due to the side affect profile, cannot be used indefinitely. Topical steroids are somewhat helpful and should always be part of the treatment regimen. If patients are allergic then immunotherapy should be considered. I like to think of immunotherapy as trying to get the some of the benefits of steroids without the side affects. In conclusion, when looking at any patient with chronic rhinosinusitis we at least need to think about fungi. Fungi are just about everywhere and fungal hypersensitivities (both allergic and cell mediated) seem to be a cause of CRS. The best way to get an accurate diagnosis is with a detailed history and intradermal dilutional skin testing to a large number of molds. We then can begin a personalized treatment based on avoidance, pharmacotherapy (antifungals), nasal irrigations, desensitization, and possibly surgery. Most patients can be helped.

Please see our section on Eosinophilic Esophagitis, as I think these disease states are pathophysiologically identicle.