Nasolacrimal duct obstruction is a blockage of the lacrimal drainage system. In children the majority of nasolacrimal duct obstruction is congenital.

Disease

Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction occurs in approximately 5% of normal newborn infants. The blockage occurs most commonly at the valve of Hasner at the distal end of the duct. There is no sex predilection and no genetic predisposition. The blockage can be unilateral or bilateral. The rate of spontaneous resolution is estimated to be 90% within the first year of life. Thus timing intervention with resolution makes this a “winner’s game”.

Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction occurs in approximately 5% of normal newborn infants. The blockage occurs most commonly at the valve of Hasner at the distal end of the duct. There is no sex predilection and no genetic predisposition. The blockage can be unilateral or bilateral. The rate of spontaneous resolution is estimated to be 90% within the first year of life. Thus timing intervention with resolution makes this a “winner’s game”.

Etiology

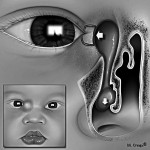

The etiology of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction is most commonly a membranous obstruction at the valve of Hasner at the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct. General stenosis of the duct is the second most common cause of duct obstruction. Congenital proximal lacrimal outflow dysgenesis involves maldevelopment of the punctum and canaliculus. Proximal outflow dysgenesis can occur concurrently with distal obstruction. Congenital lacrimal sac mucocele or dacryocystocele occurs when there is a membranous cyst extending from the distal end of the duct into the nose. The nasolacrimal duct sac is filled at birth with clear amniotic fluid.

The etiology of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction is most commonly a membranous obstruction at the valve of Hasner at the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct. General stenosis of the duct is the second most common cause of duct obstruction. Congenital proximal lacrimal outflow dysgenesis involves maldevelopment of the punctum and canaliculus. Proximal outflow dysgenesis can occur concurrently with distal obstruction. Congenital lacrimal sac mucocele or dacryocystocele occurs when there is a membranous cyst extending from the distal end of the duct into the nose. The nasolacrimal duct sac is filled at birth with clear amniotic fluid.

The fluid becomes purulent within days of birth and neonatal dacryocystitis occurs

Acquired nasolacrimal duct or canalicular obstructions can occur following trauma, viral conjunctivitis, acute dacryocystitis, and use of topical antiviral medications.

Risk Factors

Children with Down syndrome, craniosynostosis, Goldenhar sequence, clefting syndromes, hemifacial microsomia, or any midline facial anomaly are at an increased risk for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction.

History

A history of tearing, mucous discharge and epiphora of one or both eyes is typical. The periocular skin may be chapped from continual exposure to tears. Regurgitation of purulent material into the eye can cause conjunctivitis and a history of recurrent “pink eye” in an infant or young child should alert the investigator to the presence of nasolacrimal duct obstruction. The signs and symptoms are usually worse with a concurrent upper respiratory infection. An associated preseptal cellulitis is rare.

Signs

The signs of nasolacrimal duct obstruction consist of an increased tear lake, mucous or mucopurulent discharge, and epiphora. The periocular skin is sometimes chapped. The globe is usually white. When pressure is applied over the lacrimal sac there is a reflux of mucoid or mucopurulent material from the punctum.

Clinical diagnosis

The signs of nasolacrimal duct obstruction consist of an increased tear lake, mucous or mucopurulent discharge, and epiphora. The periocular skin is sometimes chapped. The globe is usually white. When pressure is applied over the lacrimal sac there is a reflux of mucoid or mucopurulent material from the punctum. Proximal lacrimal outflow blockage or dysgenesis tends to present with an increased tear lake and epiphora without mattering.

A congenital lacrimal sac mucocele presents as an initially clear bluish mass overlying the lacrimal sac. When the mucocele becomes infected and dacryocystitis occurs, there is swelling and erythema over the lacrimal sac with a palpable mass. The mass can sometimes be decompressed with digital pressure resulting in an egress of purulent material through the lacrimal puncta. If the dacryocystitis is severe, rupture of the abscessed sac through skin can occur.

Diagnostic procedures

A fluorescein dye disappearance test can be helpful in confirming the diagnosis of nasolacrimal duct obstruction. 4 A drop of fluorescein is instilled into the eyes or introduced on a moistened pledget. The disappearance of dye from the tear film after 5 minutes is observed. Retained dye in a thickened tear strip is diagnostic of an obstruction. The test is most useful if the disease is unilateral and the findings of the affected eye can be compared to those of the normal eye.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of nasolacrimal duct obstruction includes acute conjunctivitis, glaucoma, congenital anomalies of the upper lacrimal drainage system (punctal or canalicular atresia or agenesis), entropion and triachiasis.

Management

General treatment

Treatment of congenital lacrimal duct obstruction consists of initial observation for resolution followed by probing of children with persistent duct obstruction. Probing failures are treated with more aggressive surgical procedures including balloon dacryoplasty and nasolacrimal duct intubation. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy is generally reserved for intubation and balloon dacryoplasty failures.

Medical therapy

Medical management of nasolacrimal duct obstruction consists primarily of observation, lacrimal massage, and treatment with topical antibiotics. The efficacy of lacrimal massage in relieving duct obstruction is not well established. Kushner reported that lacrimal massage performed with occlusion of the common canaliculus and firm downward pressure on the lacrimal sac was more effective than gentle lacrimal massage or no massage.5 Dacryocystitis in association with neonatal nasolacrimal duct obstruction should be treated with systemic antibiotics and urgent probing of the nasolacrimal duct with attention to the need to marsupialize the membranous cyst at the distal end of the duct.

Medical follow up

Primary care doctors are usually the first medical providers to treat nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Frequently infants are referred to the ophthalmologist for surgical treatment only after a period of nonresolution. The age of the infant at referral depends on the preference of the primary care physician and also on his knowledge of the surgical practice of the ophthalmologist in regard to nasolacrimal duct probing. An ophthalmologist who performs in office probing procedures will often offer probing to families of infants 6 months or older. In contrast, the ophthalmologist who performs probings under general anesthesia or conscious sedation might wait until the infant is older because of the reluctance of families to have their infant undergo general anesthesia and to allow full chance for the obstruction to spontaneously clear.

Surgery

Primary treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction consists of NASOLACRIMAL DUCT PROBING. In this procedure a probe ranging in size from 0.70 to 1.10 mm in diameter is passed through either the upper or lower punctum following dilation of the punctum. The probe is advance along the canaliculus while exerting gentle lateral traction on the lid until it reaches the nasal bone. Then the probe is rotated 90 degrees and gently introduced into the nasolacrimal duct and advanced into the nose.

During probing a gritty feeling can be felt along a stenotic duct and if there is a distal membrane, a distinct “pop” can be felt as the membrane is breached. If the probing is performed under general anesthesia, the inferior turbinate can be infractured medially to open the area underneath it. Nasolacrimal duct patency can be confirmed several ways: 1) the distal end of the probe in the nose can be palpated with another probe 2) a small bolus of saline can be irrigated through the duct. If the infant is awake, the bolus will illicit a swallowing reflex. If the child is anesthetized the saline (colored with fluoroscein typically) can be aspirated with suction. 3) the end of the probe can sometimes be directly observed. Studies of primary surgical management have found probing to be successful in 70%–97% of cases, with many reports around 90%.6-11 The success of simple probing declines slightly with the increasing age of the child. Several investigators have reported a drop off in probing success rate with increased age, generally after 24 to 36 months.12-15 A prospective observational study of primary nasolacrimal duct probing in infants 6 to 60 months of age by the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group showed an overall success rate of 78% with no decline in the efficacy of simple nasolacrimal duct probing through 36 months of age.16 Robb has reported > 90% success rates with initial probing beyond 36 months of age.17 The success of simple probing is less for bilateral obstructions. Complex obstructions in the proximal part of the duct have a poorer success rate following probing than simple membranous obstructions at the end of the duct. The location of nasolacrimal duct probing- in office versus in a facility under sedation has been controversial with some physicians strongly advocating in office probing for its ease of performance and avoidance of general anesthesia. Others tout the small but significant risk of aspiration during the in-office procedure and state that, since in-office probing is generally performed in children less than 12 months of age, children who would resolve spontaneously are treated unnecessarily. In its observational series, the PEDIG investigators found a slightly decreased success rate for in office (72%) as compared to in facility (80%) probings in children less than 12 months of age.16 Repeat nasolacrimal duct probing is generally not a successful procedure with reported success rates of 40-60%.14,18,19

NASOLACRIMAL DUCT STENT INSERTION is used as a primary procedure or following failure of simple probing. The procedure involves nasolacrimal duct probing followed by the passage of a nasolacrimal duct probe that has a stent swedged to one end. Bicanalicular stents have two probes with an intervening stent. One probe is passed through the upper punctum and the other through the lower punctum. The probes are removed and the free ends of the stent are tied in the nose and sometimes secured with a suture. Monocanalicular stents have a plug that is seated at the upper or lower puntum while the stent hangs freely in the nose. The success of nasolacrimal duct stent insertion as a primary procedure is estimated to be between 79 to 96%.20-23 There is no difference in success rate for primary stent insertions between monocanalicular and bicanalicular stents.23 Stents are left in place for a variable period time. Migliori and Putterman had 100% resolution in 38 patients whose stents were removed at 6 weeks.27 PEDIG investigators found a deceased success rate for stent removed less than 2 months after insertion.36 Nasolacrimal duct stent insertion is often performed following a failed probing procedure with reported success rates of 66-100%.24-35 In a prospective observational study of 88 eyes undergoing stent insertion following failed probing, PEDIG found a success rate of 84% in relieving all three clinical signs of duct obstruction: epiphora, mucous discharge and increased tear lake.36

BALLOON CATHETER DILATION is used as a primary procedure or following failure of a simple probing. Standard nasolacrimal duct probing is followed by the introduction of a LacriCath balloon catheter (Atrion Medical, Birmingham, Alabama) into the duct. The balloon is inflated according to the manufacturer’s specifications and withdrawn. Success of balloon catheter dilation as a primary or secondary procedure has been estimated between 53 and 95%.37-41 A retrospective comparison between balloon catheter dilation and simple probing as a primary procedure for treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction showed no treatment advantage for balloon catheter dilation.42

NASAL ENDOSCOPY is sometimes used in conjunction with probing, stent insertion and balloon catheter dilation in the treatment of persistent nasolacrimal duct obstruction. It is also frequently used in the treatment of congenital dacryocystoceles to identify and marsupialize the intranasal cyst.43-47 In a prospective evaluation of the incidence of intranasal abnormalities in infants with mucoceles, Lueder found intranasal cysts in 22 of 22 infants examined.43 In children who failed prior nasolacrimal duct probing and in children >18 months of age at first treatment, intranasal abnormalities were identified in 8.5 and 6% respectively, most commonly nasolacrimal duct cysts, redundant nasal mucosa and distal membranes.43 Gardiner et al found no increased benefit for repeat nasolacrimal duct probing combined with endoscopy and correction of intranasal abnormalities when compared to stent insertion following a failed probe without nasal endoscopy.48

DACRYOCYSTORHINOSTOMY (DCR) can be performed from either an external or endoscopic approach. The procedure is generally reserved for children who have failed other procedures. External DCR has a reportedly excellent success rate in children (96%).49

Dacryostenosis

A very common condition in which the extreme end of the nasolacrimal duct underneath the inferior turbinate fails to complete its canalization in the newborn period and may produce clinical symptoms in 2-4% of newborns.

Absence of valves

The fold that is normally present at the end of the nasolacrimal duct or the valve of Hasner may be absent, in which case, pneumatoceles of the sac may occur and nose blowing may cause retrograde passage of air. If the valve of Rosenmüller also is absent, it is possible to blow air from the nose into the eye, and nosebleeds may produce bloody tears.

Anomalies of the sac

Although diverticulum of the lacrimal sac may occur, a congenital fistula of the lacrimal sac, which has been termed lacrimal anlage duct by Jones, is more common.

Anomalies of the puncta

Congenital atresia, supernumerary or double puncta, and congenital slits of the puncta all may occur. Lateral displacement of the puncta may occur in some congenital syndromes, such as blepharophimosis.

Anomalies of the canaliculi

Atresia or failure of canalization of the lacrimal canaliculi may occur in conjunction with punctal atresia.